Writing

I am currently working on my second fiction film feature script, working title 'Wild Child'.

I have also written and had published a number of articles about films I've made:

BROADCAST MAGAZINE ARTICLE about ‘JON SNOW: A WITNESS TO HISTORY’

It’s not every day you get to meet one of your heroes, let alone have the chance to ask them lots of impertinent questions, so for me making this film with the nation's most beloved news anchor, the recently retired, Jon Snow, was a rare and precious opportunity.

We weren’t total strangers; our paths had crossed once before with Jon doing me a huge favour when I was just starting to make films. In 2005, I’d made a no-budget documentary about an environmental protest movement called ‘The World Naked Bike Ride’ and I knew Jon was a keen cyclist. I found a general email for Channel 4 and asked them to forward it on to Jon, asking if he would do the narration for the film. I thought there’s little chance he’ll have the time to help a total newbie like me, but within a few days he’d emailed back, and soon after he rocked up on his bike at 6am, rattled through the narration in one take, giving his famous voice to our little film, completely for free.

Jump forward nearly 20 years and here I was working with him again, trying to fit a 50 year career into an hour long film. Much of importance had to be left out, but what we were able to include shows the range and depth of Jon’s journalism and his ongoing commitment to ‘go somewhere and report faithfully on what I find.’

With such a full life to cover, and in the interest of efficiency, I decided to talk at length to Ben de Pear, Jon’s editor at C4 news, to help nail down the key stories to follow in the film. Despite Jon’s very public profile, he’s a very private man and the makeup of the team was very important. Having his wife’s nephew, Charles Sibanda-Lunga, as the producer was key to establishing trust between the crew, Jon, his wife, the eminent epidemiologist Precious Lunga and their young son, Tafara. Initially, in the interests of privacy and the desire to protect Tafara, Precious didn’t want Tafara to be in the film, but over time I gained her confidence and trust, and we were able to shoot a sweet scene of Jon and 18 month old Tafara playing the piano together.

To help Jon remember the many extraordinary stories he covered, we played him recordings of his news reports to transport him back to those events. Determined to find hidden gems of archive that had not been seen before, I went to Cinelab in Slough where all the ITN film rushes that have not been digitised are stored. A very knowledgeable archivist, Matthew Harris, dug through hundreds of dusty cannisters until we found a few reels of Jon in the 1970s and early ‘80s. We viewed it all on an old Steenbeck editing machine, and some of it ended up in the final film.

In the days spent together filming, we explored his early years as a fearless war reporter, barely escaping the clutches of the El Salvadorian death-squads (unlike a number of his fellow reporters who were brutally murdered). His close connection to Africa through doing VSO in Uganda, and his wife Precious who is Zimbabwean; and the powerful resonance of his 1994 meeting with Nelson Mandela, who despite serving 27 years in prison, delivered a remarkable message to the world, of forgiveness.

The Middle East has always been important to Jon. In his reporting from the Iran Iraq war, Jon never shied away from danger for the sake of getting the story, but with the arrival of his two daughters, he decided it was time to be closer to home, taking on the job of Channel 4 news anchor. Friends wondered if he could handle being behind a desk every day, and Jon did feel being desk-bound might sometimes limit his ability to truly understand and report on breaking news, so he continued to go on location whenever he could, such as after 9/11, Hurricane Katrina, and then during the 2014 war between Israel and Palestine, so he could see first-hand what was happening with his own eyes.

One problem we encountered was that the day we were due to film an interview with former Prime Minister Tony Blaire’s main spin doctor, Alistair Campbell, the Queen sadly died, meaning he was unavailable. Despite trying to rearrange, that interview never took place.

Jon’s love of cycling provided us with another challenge, how to shoot him on the move. This is easy with contributors who drive! Our brilliant DOP, Tom Swindell, solved the problem by offering to don roller blades to film alongside Jon. Our production manager, Rita Cabral, was wary and insisted on renting a private area of a park to film in, for health and safety and insurance reasons. Once out filming, Jon declared ‘I’d never ride in a park like this’ and insisted on going to Whitehall, passed the Houses of Parliament and even got us into Downing Street to film!

He’s recognised everywhere and his address book opens many doors. And Jon is loved by so many that as we moved around the country, women in particular, wanted to talk to him and he had time for everyone. The natural performer in him loves an audience, and his ability to connect to people remains Jon’s greatest gift. Though I have to say I suffered some anxiety at times as minutes in the schedule slipped away with every engagement Jon entered into with his admiring and loquacious fans.

Despite turning 75, he scoffs at thoughts of retirement and is as busy as ever. Away from the spotlight, Jon champions many charities, none more so than New Horizon, who support homeless young people. He worked for them in his early 20’s (before becoming a reporter), and he still supports them 50 years on, auctioning off his famous lurid ties to the highest bidder. Seeing Jon on stage at this charity event, I could see that as well his love of journalism, the natural performer in him also loves a crowd, who at turns laugh with him only to then have their heartstrings pulled. This ability to connect to people emotionally is Jon’s greatest gift.

A close friend and colleague of Jon’s told me that one time she witnessed him interviewing a destitute Honduran grandmother sat collapsed in the street, and Jon treated her with the same level of dignity and respect he would have shown the Queen. No one is ever too low (or too high) to deserve his empathy and concern.

Despite a life reporting breaking news, seeing the horrors of genocide and war, and being present at many of the world’s worst natural and man-made disasters, Jon remains full of hope. As he says in the film ‘I’m an eternal optimist. I believe in the goodness of humankind. The people who are violent, the people who break things, they are on the wrong side of history. History in the end is laced with good people, with great achievements, sensational achievements, and we have to remember that and build on it.’

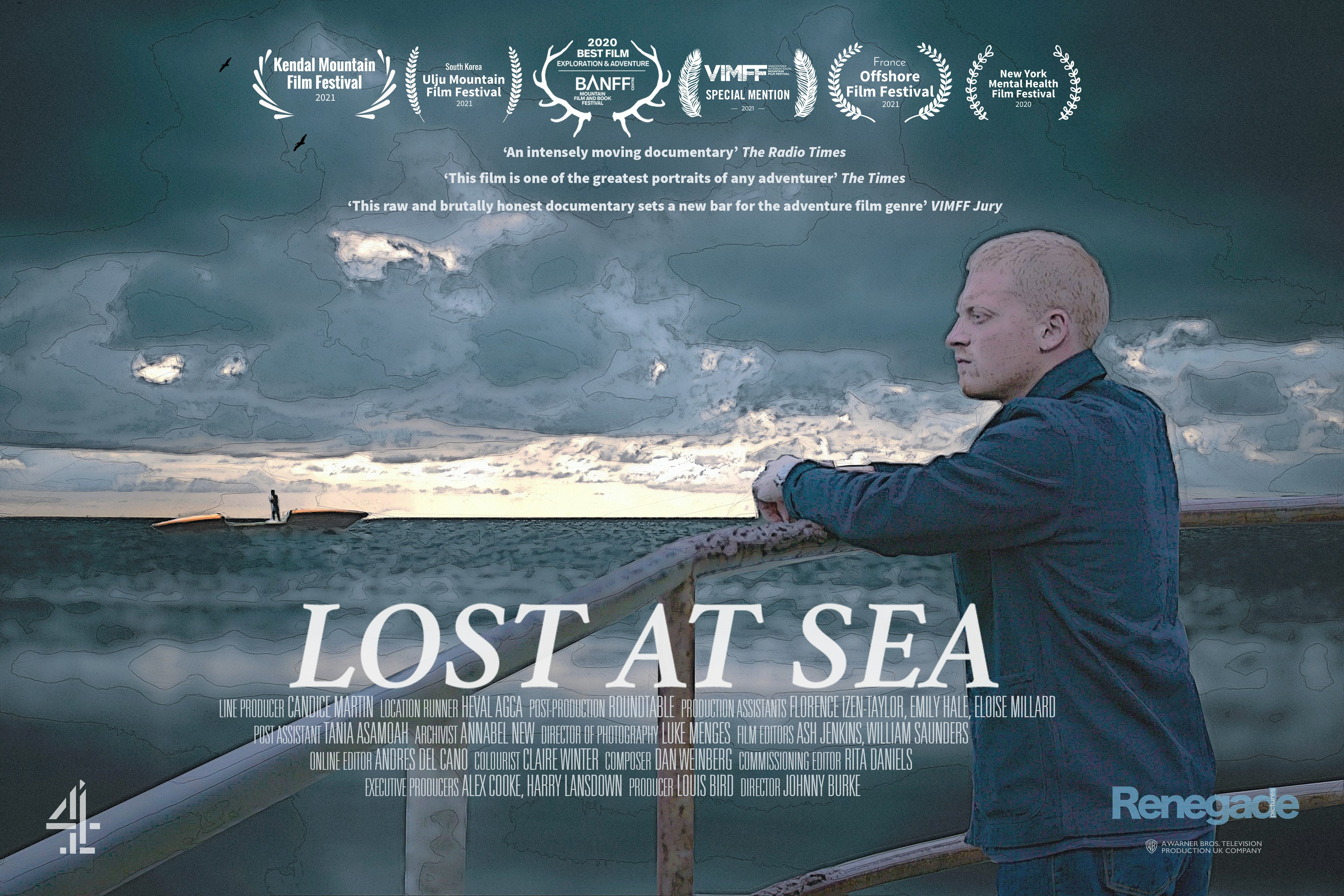

BAFTA EMERGING TALENT ARTICLE, about LOST AT SEA – MY DAD’S LAST JOURNEY

I feel that my Channel 4 film ‘LOST AT SEA: My Dad’s Last Journey’ despite being made on a small budget, managed to punch above its weight. It received nationwide radio, media and press coverage, being awarded 4-star reviews by the major newspaper reviewers. It is now starting to be accepted into festivals worldwide, such as the prestigious New York Mental Health film festival, and it has just won “Best Film - Adventure and Exploration” at the Banff film festival in Canada.

I feel like the story, broadcast at a time when we are all living under lockdown measures due to Covid 19, was able to spark an interest in a wide audience, each person drawn to the film for different reasons. With its mix of a search for adventure; the lure, and danger, of the ocean; and its deeply personal inquiry into loss and grief, people were able to respond to a number of themes in the film. Some found the story of adventure compelling at a time when they are barely allowed to leave their own homes, dreaming wistfully of being like Peter Bird, rowing the ocean alone, battling the elements. Other people were moved by his son Louis’s openness and raw emotional journey. While others were touched by Louis’ Mum, Polly for her quiet stoicism and determination to hold it all together in the face of death.

I feel that the film sits in that ‘true documentary’ tradition passed down by inspiring contemporary British directors, to name a few: Kim Longinotto, Penny Woolcock and Sean McAllister, where nothing is constructed, nothing is faked. The film’s honesty and emotion were genuine.

“This moving, intense film wasn’t really about rowing at all, though the footage of Peter setting out to sea in a woollen jumper and thick spectacles, as if pootling around on holiday, was excellent. Nothing was overplayed and I liked it for that.” The i review.

Although the film ostensibly starts out as about rowing (an obscure sport that few take any notice of), it quickly becomes much more than a rowing film. It is really about the relationship between an absent but loving father and his son, and a mother and son left to pick up the pieces. My hope with the film was that it could navigate this triangle of relationships, allowing the audience to gain understanding of, and feel sympathy for, all three main characters at different times in the story. Some will admire Peter, other’s will think he is selfish, but for me no one is simply the hero, nor simply the villain, each person in the film should be felt as complex, flawed, and real.

I hope the film also gives a unique insight into the world of forgotten amateur adventurer Peter Bird. His life and achievement do merit being remembered. He did something that no one had ever done before, rowed 8000 miles across the Pacific ocean single-handed, without a support vessel, while smashing the record for the longest a person has ever been alone at sea.

As well as setting various records, he also did something else remarkable: he filmed all of his 8 rows. This was the 1970’s, 80’s and 90’s, before the days of water-proof go-pro cameras. As well as rowing all day, surviving countless storms and cyclones which rolled his boat 360 degrees in the water like an abandoned cork, he found the time and energy to set up his 8mm, 16mm and High8 cameras, avoiding the corrosive effects of salt-water getting into the mechanism, and he gave honest and intimate updates on his progress and his challenges. Along the way, Peter may have invented a now ubiquitous type of filming: the video diary.

The fact that this footage, saved by Polly and Louis and kept in their attic for 25 years, even exists, is a remarkable testament to Peter’s determination as a cinematographer in his own right. But this footage is more than just an archive of his rows, it is also the means by which he speaks directly to his son, the son he would tragically never see grow up. It is his message from the grave to the son that, in his own way, he deeply loved, a precious and unique gift.

“It was a remarkable film made in love, but also anger, by a grieving son.” The Times, review.

‘It is Louis, candid, emotional and filled with yearning for the father he lost too soon, who holds the attention in this beautiful, bittersweet film.’ The Daily Telegraph

While admiring Peter’s achievements, the film doesn’t sugar-coat the cost of his obsession. The film makes us ask ourselves the question: how far would I go to be the first to do something? When does risk and obsession take over and get in the way of our sense of responsibility for others? The world needs people like Peter, who exemplifies the spirit of someone who keeps pushing boundaries to achieve something unique. But we also each have to face up to our own personal responsibilities, as a partner, and a parent. These questions resonate in the film, with no easy answers, and the audience go away from the film asking themselves questions about how they live their own lives, the balance they strike between acheiving personal goals and taking responsibility for others.

I also feel that creatively the film, with the support of editor Ash Jenkins, was able to break the normal chronological pattern of a documentary story and do something more interesting and revealing. We found a non-chronological structure that helped the film’s overall rhythm, (Act 1 upbeat, Act 2 dark, Act 3 upbeat, and Act 4 dark/poignant). I felt that this structure enabled the film to maintain a sense of mystery around Peter’s deeper personal motivations, while also giving the film a flow a bit like a wave, rising and falling, that felt appropriate given the subject matter.

Making LOST AT SEA challenged me in ways that helped me build my confidence in my own abilities as a director (and as a human being!). As a director, I had to learn how to plan and structure a film with a large and chaotic collection of archive, but only very few filming days to get everything we needed to tell the story.

This meant building strong relationships with all the people we would interview AND finding, and motivating, our small but amazing crew, so they were willing to work long and tough days.

When Alex Cooke at Renegade Pictures asked me to direct LOST AT SEA, she said she asked me because she felt the film needed someone who would get on well with Louis, and she thought I would be able to work well with him as the challenges Louis faced, trauma and mental health issues, were things I had also struggled with in my own life.

When I met Louis for the first time, I could see how much he was still struggling for answers, how much pain he still felt whenever he spoke about his dad. I hoped that in making the film I could both help him tell his father’s story (a source of pride for him), but also help him move beyond his trauma, and find some sense of closure. I tried my best to offer him support and guidance, a protective blanket around him, as we went on the journey of the film together.

When we filmed the scene in the hotel room where Louis listens to the tape his father recorded for him for the first time, I knew it was going to be incredibly tough. As he started crying, so did DOP Luke Menges, and me too… we were all in bits… but kept filming, even though the urge to stop and give Louis a hug was enormous. After about 20 minutes, Louis experienced a huge release of anger and pain, it burst up from being trapped deep inside his stomach and came out as rage and frustration. We were there for him throughout, and when he said ‘I cant do this anymore’ we immediately stopped filming and gave him a huge hug and a cigarette. This felt incredibly precious to me as a filmmaker and as a person, that I could help Louis go to that dark place, that he could trust me enough, to show that level of vulnerability on camera. I learnt that I could get a powerful scene AND take care of the person in the film at the same time.

6 months after filming ended, to see Louis now, he says he is changed, more settled in himself, more confident and more solid. I’m very proud to have been able to be a part of that process.

EDITING MASTERCLASS - The International Documentary Association (IDA)

The International Documentary Association (IDA) based in LA, asked me to write an in-depth analysis of the creative decisions made in the editing phase for our Emmy award-winning film, TASHI AND THE MONK:

Article to follow